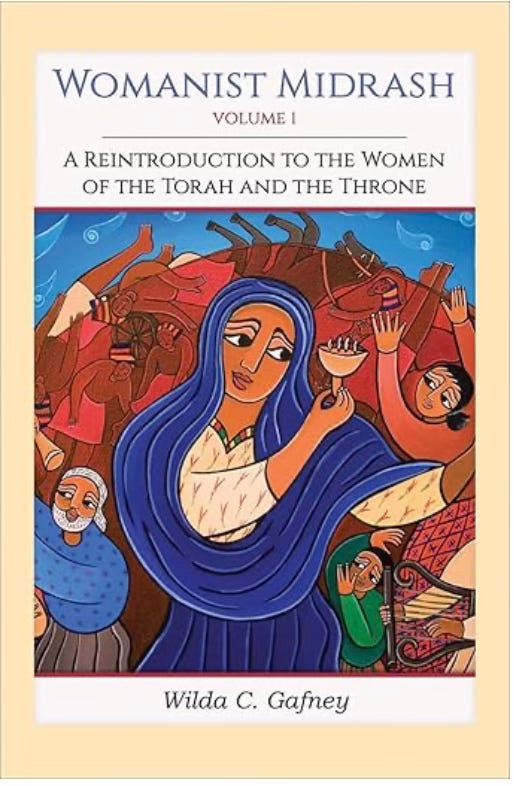

Wilda C. Gafney. The Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne. Volume 1. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press, 2017.

Some books I read I never pick up again, even if I enjoyed the experience. Some I love so much I start reading again immediately and search for more from the same author. Some I return to over and over, finding something new each time. Some become like comfort food, a safe retreat that stay close on my nightstand. And some I know so well I have large sections memorized.

But it isn’t often that a book (fiction, non-fiction, or academic) fundamentally changes me.

Wil Gafney’s The Womanist Midrash fundamentally changed how I read the Bible. Indeed, I now assign the “Appendix B: A Note on Translating” in my graduate seminars on women and religion as well as to all students taking comprehensive exams with me. Why? Just listen to how she explains her approach to translation:

“5. I use gender-specific language, for example, ‘She, the Spirit,’ rather than the gender-inclusive or neutral ‘the Spirit.’ I have determined from my work pastoring, preaching, and presiding in (Christian) congregations and teaching in college, university, seminary, and divinity school classrooms that people tend to hear neutral or inclusive language through a masculine cultural filter, so that they hear ‘the Spirit’ as ‘He,’ just as they hear ‘God’ as ‘He,’ no matter what I write or say, unless I specify ‘She.’ More than that, I believe that the refusal of translators to use explicit feminine grammar in English to translate explicitly feminine grammar in English to translate explicitly feminine grammar in the Scriptures contributes to an intentional construction of the Scriptures of Israel that is even more androcentric then they are in actuality…The Scriptures are certainly androcentric; yet they also contain woman-centered texts, explicitly feminine God-language, and inclusive passages that all too often are lost or intentionally obscured in translation.

6. Using explicitly feminine language in translation, I identify women and girls hidden in the plural forms of Biblical Hebrew. In fact, unless there is information in the text limiting the makeup of a group to male members, I translate that group inclusively, for example, ‘the daughters and sons of Israel,’ ‘the whole community, women, men, children, and the aged.’ Because so many readers/hearers of the biblical texts hear and read neutral/inclusive language as exclusive, many find it hard (if not impossible) to see and hear women and girls in the text unless they are explicitly mentioned. It is, then, critically important for womanists and feminists to name women and their presence in the biblical text so that they cannot be readily overlooked by readers, hearers, and interpreters of the text.” p. 278

Did you catch what she said? Let me break it down for you.

She uses “explicitly feminine grammar” to translate “explicitly feminine grammar” in Scripture. This doesn’t change the text when it is explicitly masculine; but it does highlight places that are often translated from an androcentric perspective. In this way, feminine language that is often overlooked and/or “intentionally obscured” is now visible.

Instead of assuming passages about the Israelite community that employ plural pronouns reference only men, Gafney assumes that (unless explicitly stated otherwise) they also include women.

Women, in short, are more visible in the biblical text. They haven’t been added to the text. Women have always been there. It is just that now, with Gafney’s help, we can see them.

The Womanist Midrash opened my eyes to how many women fill the biblical text that I had never seen before. A woman of faith herself who is also a renowned Hebrew scholar, Gafney’s approach is as accessible and pastoral as it is brilliant and erudite. I used it just last year as a teaching text in my Sunday School. I found it easy to adapt to weekly lessons and it provoked rich conversations.

So much of our modern debates about gender roles in the church stem from how conditioned we are in the Western church to not see women in biblical text. Gafney will remove your blinders.

Let me give you a Christmas example.

I assume that some of you, like me, have nativities in your home as part of your Christmas decorations. Have you ever considered how most of the figures in modern Western nativities are male? From Joseph to the shepherd to the wise men. The only female character is Mary.

Well, of course, you might be thinking. That is what the biblical text describes.

Does it?

Have you ever considered that shepherds “guarding their flocks” might include women, too? Just listen again to Gafney.

“Shepherding in the Bible is a powerful and dominant metaphor for leading the people of Israel as a civil (monarch) and religious (prophet) leader and for God’s own care of God’s people…The term has come to be virtually synonymous with clergy vocation, particularly in Christianity. Yet most readers/hearers whom I have asked cannot identify any women shepherds in the Scriptures.” p. 54.

So, Gafney explicitly identifies them.

Rachel in Genesis 29:9: “While Ya’aqov (Jacob) was still speaking with them, Rachel came with the sheep of her father, for she was a shepherd.” Gafney notes that translations often obscure Rachel as a shepherd, stating merely that she is “keeping” sheep. In this way, men are given the title of “shepherds” whereas women are just ad hoc helpers. Except, as Gafney makes clear, Rachel is a shepherd, too. (pp. 54-55)

And she is not alone. “Zipporah and her seven sisters in Exodus 2:26 and the poet-woman in Song 1:8; there is no reason to believe all of the shepherds in plural constructions are male.” (p. 86 footnote 66).

Female shepherds are present in Scripture. Not only does this challenge our androcentric perspective of shepherds (such as potentially in the nativity of Jesus), but it also challenges our assumptions about biblical women.

Rachel, for example, is presented as shepherding alongside male shepherds.

“There is no apparent concern about Rachel working in proximity with these men as a woman in general or because she is both marriageable and not yet married. Rachel is not described as being in the company of other women (shepherds, servants, or sisters). The stereotype of biblical women being confined to the home, to women’s company, avoiding the public sphere and the company of (unrelated) men, falls on its face with the introduction of Rachel in the Bible.” (p. 55)

See what I mean? I bet you never look at another nativity without thinking about female shepherds.

Take up and read Wil Gafney. I promise you will be changed.

Thank you, Beth, for including Wil Gafney’s midrash in your book list. She is indeed a powerful voice in biblical interpretation, offering scholarly explanations for reading texts more inclusively. I am awed by her scholarship and deep dive into the usage of biblical language. We can all learn from her work, as your students are.

This is such a wonderful book and resource! Beth, I deeply appreciated your recent piece on Bathsheba. It wasn’t until I read Gafney’s ‘Dominated by David’ chapter that I realized Bathsheba’s innocence and the harm caused by being taught to think otherwise. I appreciate your work on women’s roles in the church and within the scriptural narratives. Blessings to you!