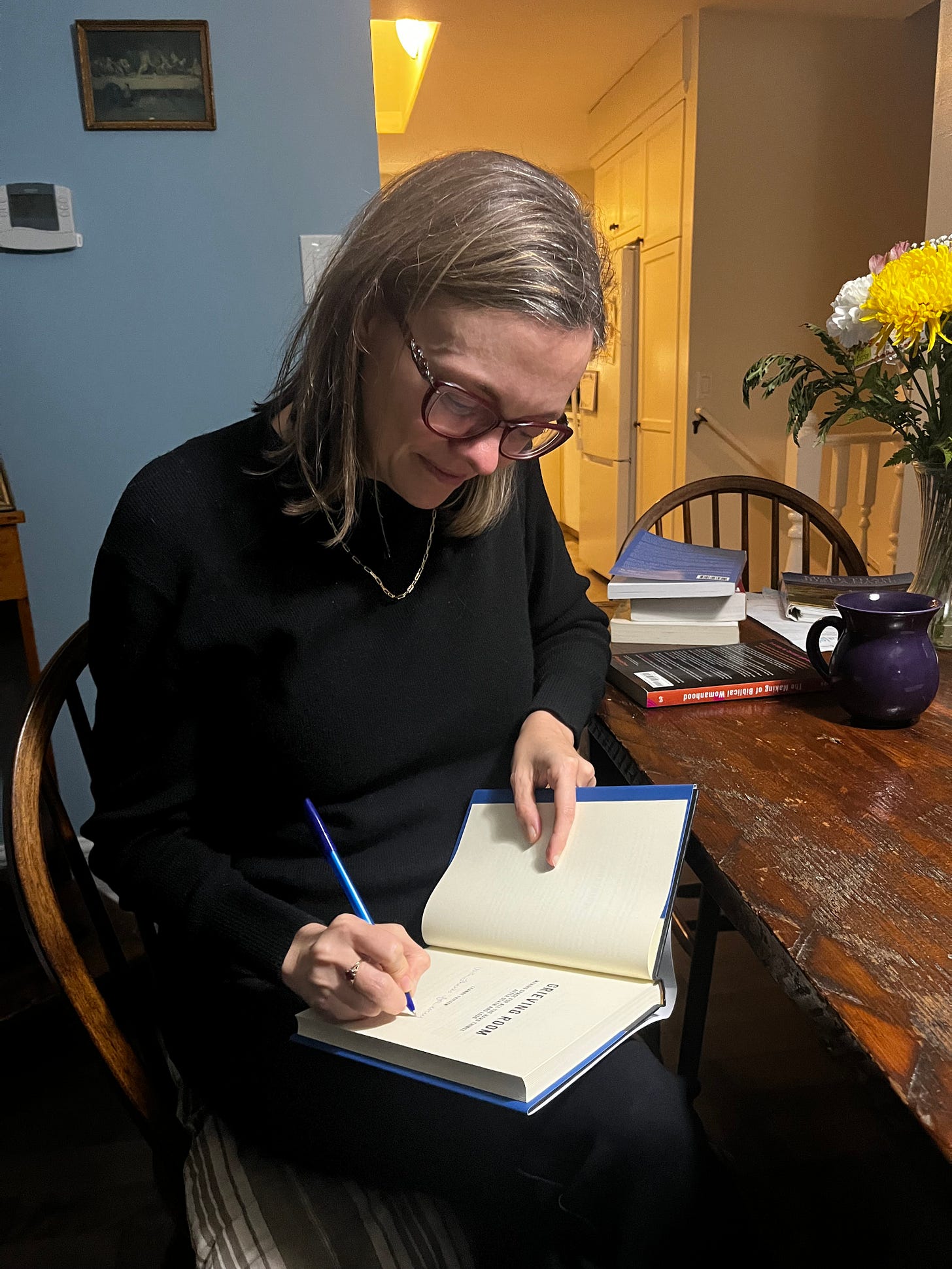

For those of you grieving, with loved ones grieving, and/or pastoring people in grief--You will want Leanne Friesen's new book

An excerpt from Grieving Room: Making Space For All The Hard Things After Death and Loss

One month ago I traveled to Toronto, Ontario, Canada for the first time in my life. I was attempting to verify a story I found in the Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives last June. The trail led me to Canadian Baptists of Ontario and Quebec. Which is how I met Leanne Friesen. I went to Canada for professional reasons and I left Canada with a new and already dear friend. Leanne Friesen is the Executive Minister of Canadian Baptist of Ontario and Quebec (CBOQ). While the Southern Baptist Convention last June was kicking out churches with female pastors, CBOQ was voting a female pastor as their executive minister. There are so many wonderful things I could tell you about Leanne and her family (and I probably will in a later post), but for now I want to share with you her new book. As someone in ministry myself, I can tell you Leanne’s pastoral voice and personal narrative strikes exactly the right tone for those dealing with grief.

Reprinted with permission from Grieving Room: Making Space for Grief, Loss, and All the Hard Things by Leanne Friesen copyright 2024, Broadleaf Books.

In 2013 my sister Roxanne died of melanoma. Of all the things that people said to me during her dying, one stands out to me most: the words spoken by a well-meaning person hoping to comfort me. I don’t remember who said these words, though I know it was a woman. I don’t remember what day they were said, though I can picture exactly where I was standing when I heard them. I remember what I was wearing, what the weather was like that day, and the sound of the people buzzing around us as we talked. And I only have to pause for a moment to relive the confusion I felt as I processed what was happening.

My sister was nearing the final days of her life after eight years of living with cancer. She had stopped treatments, planned her funeral, and made arrangements for palliative care. It had been several days since she had been coherent, weeks since she had been without pain. My whole family was already grieving, and I was smack-dab in the middle of the trauma of the slow, painful death of a sibling, one that I could barely process.

At the church where I work as a pastor, I was mingling with congregants in the lobby after our Sunday service. As happened often in those days, someone asked me how Roxanne was doing. I started to answer: “Well, she’s dying—”

With a mixture of horror and dismay, this person put her hand over her mouth. “Don’t say that!” she said vehemently.

I was temporarily stunned, shocked by her statement and confused by how I should respond. “What do you want me to say?” I asked, utterly bewildered.

“Well, it’s just . . . you have to have hope!” the woman said.

I debated walking away and taking my aching soul with me, but I wanted to defend myself. I wanted this woman to understand why I absolutely needed to say what I had said. “I do have hope,” I answered, trying to keep my emotions in check. “I have hope that if we live, we live to the Lord and if we die, we die to the Lord, and that whether we live or die, we belong to the Lord.” My voice stayed surprisingly even as I shared this favorite Scripture that had brought me hope during this painful season. And maybe now it would help her get the hint to back down a bit?

“But you can’t give up!” the woman pressed on, clearly distraught.

I don’t remember what I said next. But I remember that I was baffled, and I was hurt. What did this person even mean? What did “not giving up” look like? Was it praying for a miracle that I had accepted was not going to happen in this lifetime? Was it refusing to admit that my sister’s death was imminent? Was it reciting platitudes like “She can still beat this,” or pretending, for this woman’s sake, that Roxanne’s health was better than it was? How was it “giving up” to accept the reality that my sister was going to die?

I heard the message loud and clear on that Sunday in the spring of 2013: There is no space for your grief here. There is no space for death. There is no room for your despair.

The woman was okay with miracles. She was comfortable with optimism. She could make sense of one version of hope. But death? Not so much.

I know she meant well and that she was only trying to protect me from the pain that my sister dying would cause me. Suggesting that the death might not happen was meant to uplift me. But in that moment, I needed space for a pain that wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon. I needed to name the huge thing that was right in front of me: the thing that consumed all my waking thoughts and kept me up at night. I didn’t need to be told to “not give up.” I didn’t need to be told to “have hope.” I needed grieving room. In a culture of relentless optimism, I was learning that this space was going to be hard to find.