Part II: Episode I--How Do I Understand 1 Timothy 2?

a.k.a. my ongoing conversation with my husband (this is the first of two posts)

“Let a woman learn quietly with all submissiveness. I do not permit a woman to teach or to exercise authority over a man; rather, she is to remain quiet.”

1 Timothy 2:11-12 ESV

My husband isn’t a yes-man. To no one’s surprise, I am not a yes-woman either. When we disagree, we say we disagree. Sometimes we do this better than other times. I can say that our ability to disagree with grace has improved during the twenty-five years of our marriage. I can also say my husband sharpens me. My writing is better because of him (and dare I say his sermons are better because of me :).

Which brings me to 1 Timothy 2:11-15. After reading my first post, my husband pointed out I hadn’t answered my question. I pointed out that was my point—I think fixating on 1 Timothy 2 is the wrong question (see my earlier post).

But…. I could see his point, too.

1 Timothy 2:11-15 is a linchpin for complementarian arguments. William Witt writes in his Icons of Christ, “ it is the only passage in the entire Bible that on a literal reading might seem to exclude women from teaching or having authority over men. Moreover…the passage appears to be transcultural in that it grounds its argument in the order of creation itself,” (p. 155).

Which means I hadn’t offered help to folk struggling with the only passage in the Bible that seems to limit female teaching as well as seemingly grounds male authority in creation. It is no wonder that complementarian scholars like Tom Schreiner appeal to the importance of 1 Timothy 2:11-15.

While it is true I find folk annoying who weaponize 1 Timothy 2, it is also true I can’t ignore the scripture. It is there. I should deal with it.

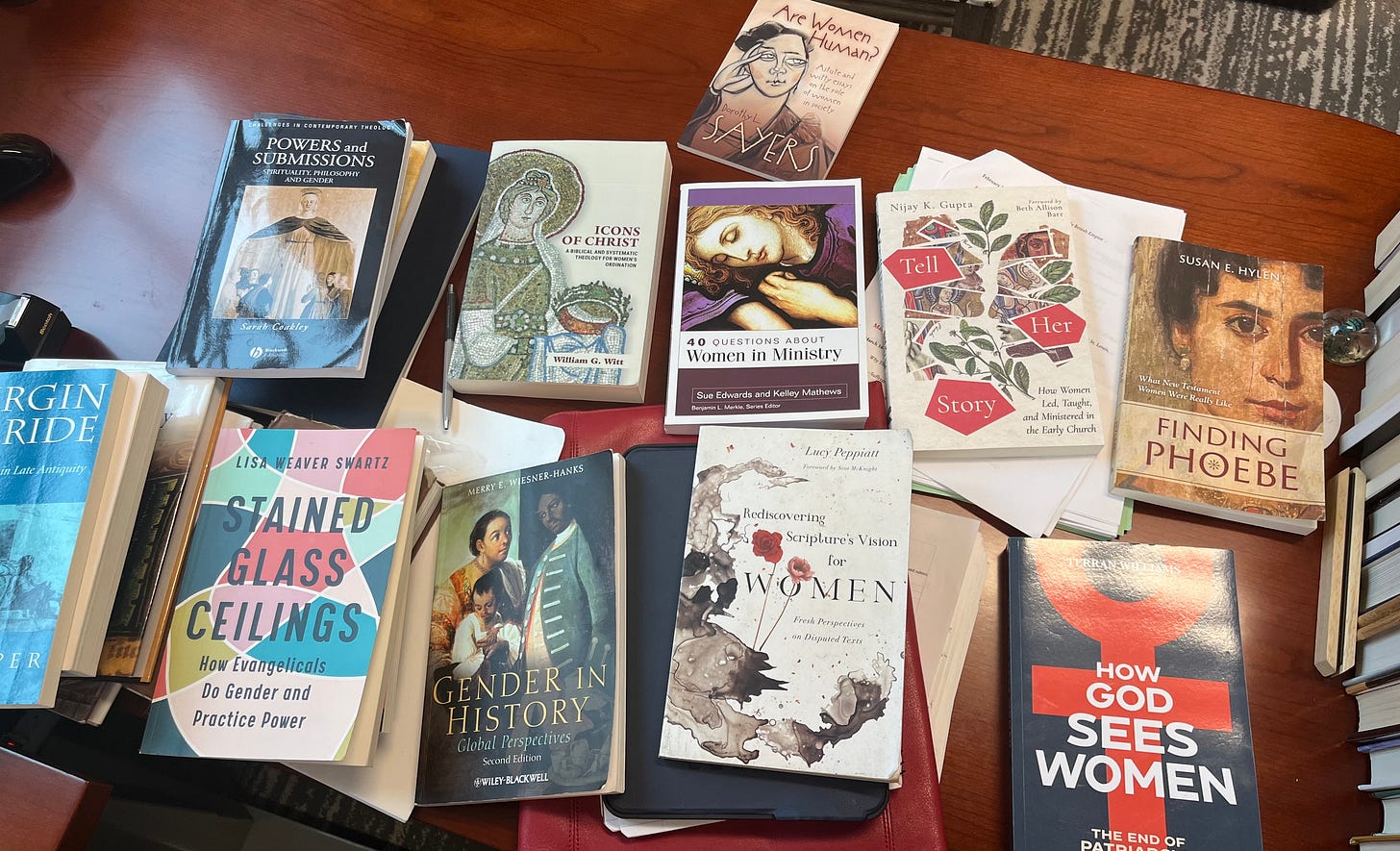

Today I will take on verses 11-12 and next time I’ll take on verses 13-15. There is so much excellent scholarship I could cite here—from Scot McKnight to Beverly Gaventa to Cynthia Long Westfall, just to name a few. For this first post, I’m going to focus on a new book by Nijay Gupta (Tell Her Story: How Women Led, Taught, and Ministered in the Early Church, which is forthcoming in March) and the scholarship of Susan Hylen (she also has a brand new book Finding Phoebe: What New Testament Women Were Really Like).

So what do I think?

First, we can’t deny the pervasive reality of biblical patriarchy. As Susan Hylen writes, “the New Testament reflected social norms that viewed women as inferior and insisted upon their silence,” (Women in the New Testament World, p. 158). We can’t argue otherwise.

Second, I agree with complementarians: I think Paul is telling a group of women to stop teaching. But, unlike complementarians, I do not think Paul’s words are broadly applicable. I do not think patriarchy is the end of the story. If I may channel the spirit of The Making of Biblical Womanhood, I think we can read 1 Timothy 2:11-15 more judiciously than as a “transcultural” and trans-chronological prohibition.

So let’s read it differently.

Nijay Gupta reminds us that the pastoral letters (1 & 2 Timothy & Titus) were not “comprehensive instructions for clergy or a universal guide for all churches,” (p. 166). Each letter provides culturally relevant guidance for navigating a range of situations. 1 Timothy 2, for example, expresses much concern over false teachings. There isn’t enough evidence to know for sure what was going on in Ephesus —although disruptions caused by the “new women” movement and/or the influence of the cult of Artemis are both plausible (Gupta summarizes these well). What we do know for sure is that Paul is calling out women who are exercising inappropriate teaching authority (very possibly connected to false teaching). We also know that cultural norms would have yawned at Paul telling women to sit down and shut up.

The question, then, isn’t what Paul is saying.

The question isn’t even why Paul is saying it.

The question is to whom Paul is saying it. Is he providing transcultural guidance to all women in all circumstances, or is he providing culturally relevant guidance for particular women in particular circumstances?

Let’s consider the evidence.

Controlling speech (silence) was a cultural norm expected for both women and men; it was also valued for leadership. Hylen reminds us that 1 Timothy 2:9-15 is sandwiched specifically by the important virtue of self-control (which included controlling the tongue, i.e. being silent). The word for self-control is referenced in verse 9 and again in verse 15. Even more interestingly, this virtue (self-control) is not gendered female. It is a qualification for church leaders (both male and female) to exemplify self-control in their speech. Hylen offers us additional New Testament examples of this virtue (Finding Phoebe, pp. 150-166 and Women in the New Testament World, 152-154).

1 Corinthians 14:26-33: “if there is no interpreter, the speaker should keep quiet [have self-control] in the church and speak to himself and to God…..Two or three prophets should speak, and the others should weigh carefully what is said. And if a revelation comes to someone who is sitting down, the first speaker should stop [have self-control].”

1 Timothy 3:2-3, 8, 11: “Now a bishop [elder] must be above reproach, married only once, temperate, self-controlled, respectable, hospitable, an apt teacher, not a drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, and not a lover of money…Deacons likewise must be serious, not double-tongued, not indulging in much wine, not greedy for money…Women likewise must be serious, not slanderers, but temperate, faithful in all things…”

Note that neither of these passages are specifically addressed to women. Note that, in 1 Timothy 3, the qualifications for male and female deacons are parallel (btw there is no plausible reason to exclude women as deacons here; there just isn’t). Note also how 1 Timothy 2:11-12 reflects similar virtues as found in 1 Timothy 3 (yes—it says women are not to “have authority” over men, but just wait). Leaders are to exercise self-control in regards to speech, be respectable, be trustworthy, and not be intemperate.

Just think about that.

The women in Ephesus are asked to exercise self-control in their speech and submit to learning (presumably to their teachers who are not actually gendered male in 2:11). Exhortations to control the tongue are found throughout the New Testament. While not gender specific, these exhortations are specifically associated with leadership in 1 Timothy 3. Susan Hylen nails the significance of this in Finding Phoebe (p. 98).

“The language of 1 Timothy reflects a social context in which women who were honored for being self-controlled could still exercise various forms of leadership in their households and communities. The historical context should shape our understanding of 1 Timothy. It was common to see women in leadership roles who also fulfilled the social rules of modesty [self-control]. Modesty did not simply limit women’s leadership; it was also seen as the basis of good leadership.”

Could it be that instead of 1 Timothy 2:11-12 being used exclusively to limit women’s leadership, it should also be read as teaching women how to be better leaders? Just like male leaders, they should control their speech and learn before they teach.

Female submission was a cultural norm. Directives for women to submit shouldn’t surprise us. What should surprise us is rigid, sweeping interpretations of these directives that do not reflect historical nuance. I’ll give you two examples of why historical nuance matters.

Silence and submission were never “a hard-and-fast rule” for women in the Greco-Roman world (Finding Phoebe, 152). They just weren’t. It depended on the situation as well as the social rank and relationship of the participants. Hylen writes that, “silence was a virtue for any person who was in the presence of those society considered of higher social status. This was true of women when they were among men of higher status. But it was also true of men when they were in the presence of people of high standing,” (p. 152). If we combine this observation with the one above (importance of silence for leadership), it is possible (probable?) that 1 Timothy 2:11-12 was a response to unlearned women attempting to domineer men in a socially inappropriate way. Paul told them to stop it.

Whatever the case, we know for sure that social rank impacted the code for silence and subordination. Yes, some women had to be silent before some men. But some men had to be silent before some women. Yes, women were generally subordinate to men. But some men would have been subordinate to women who were social superiors, (Finding Phoebe, pp. 152-155). In no situation would any Roman man be regarded as having authority over any Roman woman. So why in the world would we interpret 1 Timothy 2:11-12 without this nuance, especially considering the plentiful evidence of women teaching and exercising authority throughout the New Testament?

The verb translated as “exercise authority” or “assume authority” in 1 Timothy 2:12 is “an extremely rare word in this time period,” (Nijay Gupta, Tell Her Story, p. 170). Gupta deals with this word brilliantly. I don’t want to steal his thunder (just order his book), but let me give you two of his points.

First, he reminds us that from the sixteenth-century through the 1970s, the word “authenteo” (how do I add accent marks into substack?) was translated mostly as “usurp authority” or “domineer/dominate”. It wasn’t until after the conservative resurgence and the rise of “biblical womanhood” that the word began to be translated as “exercise authority/assume authority.”

Convenient, don’t you think? Until recently, 1 Timothy 2:12 read something like this: “I don’t let women take over and tell men what to do,” (Eugene Peterson’s translation in The Message, as quoted by Gupta, p. 170). Instead of rebuking women for being domineering, translations like the ESV now forbid women to have leadership over men.

Second, he reminds us (building on the work of Cynthia Long Westfall) that “authenteo” wasn’t used to indicate ordinary authority in the first century world (hence the history of translating it as “usurp” and “domineer”). Words used to indicate ordinary authority were much more common than “authenteo.” Paul didn’t use the more common words. Instead, as Gupta points out, he used an extremely rare word with a specific connotation for dominating/overpowering. As Gupta writes, “It simply can’t mean ‘have authority’ in a neutral or positive sense. It stretches logic too far an doesn’t fit how interpreters from the ancient world and most of the modern world have read the word. It is much more likely that Paul was appealing to a relatively rare word that carries a sense of abuse of power to prohibit women (who had succumbed to false teaching) from taking over the church and seeking to put men ‘in their place,’” (p. 173).

In short, the word Paul chose expressed the abuse of authority in the New Testament world—not the everyday authority of church leaders (Gupta, p. 172).

Let’s put this all together. In the first century world of the New Testament:

Controlling the tongue (quietness/silence) was a gender-neutral virtue encouraged for leadership.

Women in general owed more submission/silence than men did (thank you patriarchy), but it was never a “hard-and-fast rule.” A ban limiting all women, regardless of social status, from having authority over any man did not exist.

The word used by complementarians to forbid women leadership was not used that way in the first century world. In the first century world it was used to express abusive power.

What do I think 1 Timothy 2:11-12 means?

I think it means that Paul was telling some women to stop teaching. Even without knowing the specific circumstances in Ephesus, the New Testament shows this can’t have been a widespread ban (think Romans 16, Priscilla, Lydia, etc.). An exploration of New Testament culture shows that silence was a common virtue for both men and women, expected of good leaders. An examination of first-century words shows that it is much more likely women were being told not to abuse authority rather than being forbidden to have authority.

I think it means that the 2,097 Baptist pastors and seminary professors who have signed the SBC “call to unity” to disfellowship churches that “abide women in the pastoral office” because of how they read the pastoral epistles (1 Timothy 2 & 3 and Titus 1) are making a claim not supported by historical evidence.

I think it means that, 21 months after the publication of The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth, the historical evidence for my thesis is even stronger: complementarianism is about patriarchy and patriarchy is about power.

I think evidence for my secondary argument is stronger too: neither have ever been about Jesus.

I’m hanging out with Kristin Du Mez this week, as well as Jemar Tisby, Beth Moore, and maybe even Kaitlyn Schiess. I’ll try to finish the second part of this, but it may be early next week before I do.

You're doing important work, Beth. I'm so grateful for your scholarship and courage. Thanks for pointing out the previous scholarship on i Timothy 2: 11-15 too.

I agree with Nijay Gupta and you that these verses are not "comprehensive instructions for clergy or a universal guide for all churches" and all time.

Yes, back in 1974 we were working hard on the translation of "authenteo"--and trying to spread the word that "usurp authority" was a better translation than "exercise authority" for crying out loud.

Yes, "complementarianism is about patriarchy, and patriarchy is about power."

Since 1974, I'm no longer convinced that Paul wrote 1 and 2 Timothy. Many literary pieces use the name of a more important voice (whom the author supposes would support the views he is writing).

I also like the thesis that these letters are part of an ongoing debate among Jesus followers. Some believed (with this author) that a certain group of women should stop teaching and called their teaching "old wives' tales." Others believed with Paul in Gal. 3:28 that gender rules are now transcended in Jesus the Messiah, along with ethnic and economic dividing lines. That's the argument on 1 Timothy 2 that makes the most sense to me these days.

How can we get people to stop using the Bible like a weapon? I see everyday in the work I do as a hospice chaplain. It's depressing and upsetting to me how often people use one verse like a weapon. KEEP UP THE GOOD FIGHT!!!! I am so grateful for you. (and my wife is too)